PHOTO GALLERY

The mountain line had

automatic block signaling between Vasona Junction and Santa Cruz. Though

the signals are long gone several of the concrete signal bases are still

in place along the line. On October 25, 1984, SP GP9E 3838 parks next to

one such base at the south end of Mission Hill tunnel in Santa Cruz. (Jon

Pullman Porter)

Approaching Tunnel 5

from the cab of Big Trees CF7 2641. This bore has since been daylighted

by SCBT&P.

(Ken Rattenne)

On March 20, 1988 Santa

Cruz Big Trees & Pacific CF7 2641 leads a Central Coast excursion near

Olympia. This may have been the first passenger train through Olympia since

No. 34 with the last train from Los Gatos in 1940. (Ken Rattenne)

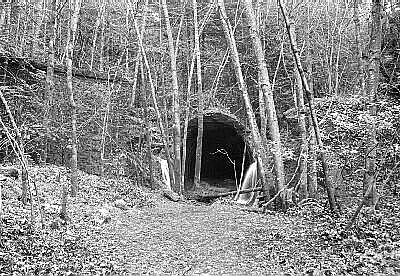

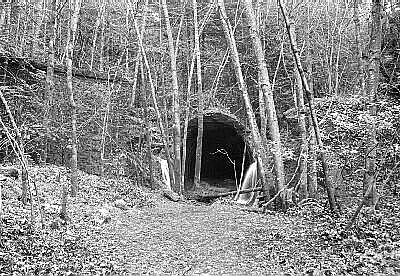

Deep in the Santa Cruz

Mountains on February 7, 1984, the summit tunnel at Wrights shows the effects

of 44 years of nature's reclamation efforts. (Jon Pullman Porter)

Three

Suntan Specials wait out the day at the Santa Cruz Yard during the late

1930s. In only a matter of a couple of years these trains will lose their

mountain crossing. click the photo to enlarge. (Rattenne Collection)

|

After

a devastating winter storm in 1940, SP abandoned their line over the Santa

Cruz Mountains.

June 4, 2000 marked the 60th

anniversary of the abandonment of Southern Pacific's line over the Santa

Cruz Mountains between Los Gatos, a small community in the foothills south

of San Jose, and Olympia, 8.8 miles north of Santa Cruz. Officially, the

line was the Los Altos-Santa Cruz Branch on the San Francisco Subdivision

of the Coast Division.

The

route had been completed in May of 1880 by the South Pacific Coast Railroad

as part of its narrow-gauge line between Alameda and Santa Cruz. SPC was

taken over by SP in 1887 and the line was standard-gauged around 1907.

By the late 1930s the line was down to one through freight a day in each

direction. Passenger service, though by now loosing $30,000 a year, was

still provided between San Francisco and Santa Cruz by trains 31, 32, 33,

34 and 47.

On

the afternoon of February 26, 1940 the line was closed by mud slides and

wash-outs following several days of turbulent storms. Train #34, the 11:26

a.m. arrival from San Francisco, likely had the dubious distinction of

being the last train to run over the "hill," ending 60 years of operations.

Train #33, the evening train to San Francisco, ran via Watsonville Junction

that night. Regular Santa Cruz passenger service ended after that.

SP

initially planned to reopen the line, and even had the route listed in

the March 30, 1940 timetable. However, facing an estimated $55,000 in repairs,

coupled with competition from newly-opened Highway 17, SP threw in the

towel and filed for abandonment of the 16?mile section between Los Gatos

and Olympia.

SP initially planned to reopen the line,

and even had the route listed in the March 30, 1940 timetable.

Once

permission was granted on June 4, the rails were pulled up, with much of

the right-of-way being taken over by the water district. Lexington Dam

was built in 1952, displacing the former town sites of Alma and Lyndon

with a two-mile-long reservoir. Highway 17 was rerouted around downtown

Los Gatos in 1956, severing the route SP had taken from the station down

into Los Gatos Canyon. In 1958 the line was further cut back with the abandonment

of the 2.5 mile section between downtown Los Gatos and Vasona Junction.

In

1982 SP halted service between Eblis siding in north Santa Cruz and Olympia,

but left the 7.7 miles of track in place. Even so, when tourist operator

Santa Cruz, Big Trees and Pacific took over the line just three years later

they encountered fallen trees across the tracks, sections buried by mud

slides, shifts in track alignment (the line crosses the San Andreas Fault

between Wright's and Laurel), erosion of the right-of-way that left track

and ties dangling in the air, and pools of water from clogged drainage

pipes. Basically the same maintenance headaches railroaders have faced

since the mountain line opened a century earlier.

Despite

all this, 60 years later parts of the abandoned line remain remarkably

intact. Tunnel portals, crossties, trestle supports, signal bases and other

relics are visible along the overgrown right-of-way. The route along Los

Gatos Creek is now part of a hiking and bike path as far as the reservoir.

Trestle supports near Lyndon and Aldercroft are still in place, but today

carry large water pipes instead of rails. The towering concrete bridge

piers at Wright's (or Wright, as it was listed in SP timetables in later

years), stand abandoned amid dense forest growth but still display, in

faded paint, their admonition not to stand too close as "…rocks etc. might

fall from passing trains."

Much of the mystique of the mountain line involves the tunnels

on the route -- nearly three miles of bores were required over the 24-mile

distance between Los Gatos and Santa Cruz. The longest tunnels, the 6,157

foot summit tunnel at Wright's and the 5,793 foot tunnel between Laurel

and Glenwood, have especially become part of the legend and lore that has

always surrounded the Santa Cruz Mountains.

60 years later parts of the abandoned line remain

remarkably intact.

Though the line passed into history in 1940, its ghost

offers the enticing prospect of relieving traffic congestion on Highway

17, while haunting Santa Cruz residents with the fear of their town being

overrun by tourists and commuters. Embraced by transportation planners

in Santa Clara County and held at arm's length by their counterparts in

Santa Cruz, studies and proposals to re-open the line have appeared on

a regular basis for the past 30 years.

A

1971 study by Lockheed determined that 37 percent of the original route

was still in use, 27 percent could be easily restored and 36 percent would

require new construction, principally around Lexington Reservoir and Los

Gatos. The cost was estimated at $50 million.

Most proposals have advocated the use of light-rail electric

trains. One of the latest plans proposed an $8.20 toll on Highway 17 to

fund the estimated $500 to $600 million it would cost to reopen the line

as a transit corridor. Santa Cruz officials vetoed revival proposals in

1977, 1982 and 1991 and have indicated a reluctance to participate in new

studies.

One

proposal that seems to be gaining momentum is the restoration of passenger

service via Watsonville Junction, the route the Suntan Special used after

the mountain line was severed. The Suntan covered the 70 miles between

San Jose and Santa Cruz in two hours, just 24 minutes longer than trains

took over the mountain line. Transit times would be close to the old running

time over the mountain if the Watsonville-Santa Cruz line could be upgraded

to allow 35-40 mph speeds. This route is attractive since Monterey is clamoring

for passenger service, and could possibly pool equipment with a San Jose-Watsonville

Junction-Santa Cruz operation.

|

|

Sources:

-

A Centennial South Pacific Coast by Bruce MacGregor

and Richard Truesdale, published by Pruett Publishing Company, Boulder,

Col. 1982.

-

Narrow Gauge Portrait South Pacific Coast, by Bruce

MacGregor, published by Glenwood Publishing, Felton, Cal., 1975.

-

California Central Coast Railways by Rick Hamman,

published by Pruett Publishing Company, Boulder, Col., 1980.

-

Highway 17 The Road to Santa Cruz by Richard A. Beal,

published by The Pacific Group, Aptos, Cal., 1991.

-

San Francisco Chronicle, April 9, 1993

-

Santa Cruz Sentinel, October 29, 1971

|